By Michael Paciotti, CFA

“I continue to believe that the American people have a love-hate relationship with inflation. They hate inflation but love everything that causes it.” – William E. Simon1

For much of the past nine months, investors, media outlets, and practitioners have been hyper-focused on the concept of a soft landing and, similarly, a pivot back to a world of rock bottom interest rates. For context, achieving a soft landing would include two objectives. First, inflation returning to the Fed’s target rate of 2%. Second, arriving there with little to no pain inflicted to the economy. Doing either individually is not much of a tall order. The trick is in doing both simultaneously. With the recent issues surrounding the global banking system taking center stage, the difficulty of achieving this goal has become apparent.

[wce_code id=192]

To better understand this, let me spend a moment on inflation itself. While we can and have debated the causes of inflation, regardless of the source, inflation manifests itself as a result of excess demand at a given level of supply, with price being the equalizer to bring supply and demand into balance. Likewise, changing price levels impact either the supply of goods offered at a given price or the demand for them. Simplistically, think about the inflation/supply-and-demand relationship as a balloon. One can compress one area only to see another get bigger or smaller. With inflation, each variable is a release valve impacted by movements in the others. Given this very basic explanation and analogy, there are two avenues to squash inflation. One can increase supply or reduce demand to bring the equation back into balance at a lower price level.

For some time now, many have argued that inflation today is nothing more than disruptions in the supply chain that will normalize over time. Today that argument has morphed into an argument that is centered around supplies being constrained due to tight labor markets. Sound plausible? Certainly. I am here to tell you that empirically neither of those arguments can currently be supported by data. Inflation is the result of excess demand. We are simply out consuming our productive capacity and as a consequence, further rate increases are warranted in this inflation fight.

Now, the global banking system can be a bit of a fragile beast. With trillions of dollars in deposits, commercial and residential loans along with currencies flowing through its pipelines, it is surprisingly only as strong as the collective belief and confidence that deposits will be there and loans will be repaid. While the events of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) were in fact unique, they brought to light issues that may exist in other less specialized banks. That is, deposits, above the $250,000 FDIC threshold, are nothing more than a loan to that bank. They are not guaranteed and are only as good as the creditworthiness of the bank, or the mercy of the regulators to protect the depositor beyond what is required. While the issues surrounding SVB may have been unique, they shined a big bright light on the uninsured deposits that are commonplace in all banks. It didn’t take much more than this for doubt to start to creep in and deposits above the FDIC limit to exit small and less stable banks in droves for larger institutions. While there are many solutions to this, one being to ease financial conditions to protect bank balance sheets, what happens to inflation if you do? Conversely, does this inflation fight have to occur at the expense of our entire financial system? I intend to discuss both in this quarter’s Market Insights, The Soft Landing Facade.

Tight Labor – Causing Supply Issues?

Getting back to the concept of inflation and optimistically the soft landing, for prices to remain stable, we must reach a level where the demand for goods is equal to the supply of goods at that price. If it is our desire to protect demand (i.e., no recession), then supply is theoretically our only option. Unfortunately, theory is likely the only place where the supply side can fix this issue, as reality paints a much different picture.

Getting back to the concept of inflation and optimistically the soft landing, for prices to remain stable, we must reach a level where the demand for goods is equal to the supply of goods at that price. If it is our desire to protect demand (i.e., no recession), then supply is theoretically our only option. Unfortunately, theory is likely the only place where the supply side can fix this issue, as reality paints a much different picture.

One of the primary arguments supporting inflation as a supply side issue is that scarce labor is impacting the availability of goods and services. If not for scarce labor, supplies would be available in large quantities and inflation would not be an issue. Therefore, the Fed’s actions which impact demand are unnecessary. Fix supply and you fix inflation. To support this claim, proponents will often point to the historically low unemployment rate of 3.6% and a participation rate of 62%. The error here is not seeing the forest for the trees.

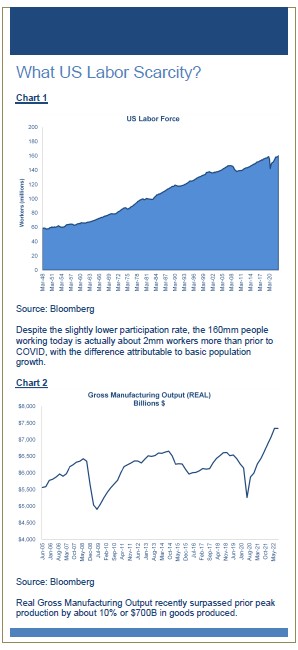

First, for those that are not familiar, participation rate is defined as the percent of the population that is either working or actively seeking work. Today the participation rate is about 62% which is lower than the historical peak of 67%, a level we achieved just prior to the bursting of the internet bubble. For more recent context, the participation rate just prior to the onset of COVID was 63%, with the difference of 1% amounting to about 2 million workers. While this may seem like a large number, let me remind you that the total US labor force is about 160mm workers, as seen in Chart 1. Despite the slightly lower participation rate, the labor force of 160 million today is actually about 2 million workers larger than prior to COVID, with the difference attributable to basic population growth. This has translated directly to Real Gross Manufacturing Output (Chart 2) surpassing prior peak production by about 10% or $700B in goods produced. Said differently, we are employing more workers and producing more today than we did prior to COVID. If supplies are in any way hampered or limited by labor or lingering supply chain issues, both of these data points seem to suggest otherwise.

Excess Demand is Driving Hiring

A moment ago, I pointed to the overall size of the current labor market, as compared to its history, as an indicator that a lack of labor is not driving scarcity of available goods. I backed this up by showing the $700B real increase in the supply of goods. While all of this is true, hiring remains difficult for businesses.

A moment ago, I pointed to the overall size of the current labor market, as compared to its history, as an indicator that a lack of labor is not driving scarcity of available goods. I backed this up by showing the $700B real increase in the supply of goods. While all of this is true, hiring remains difficult for businesses.

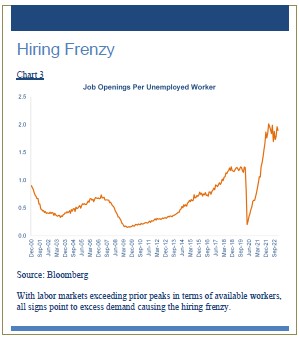

With unemployment at record lows, there are now nearly two jobs available for each unemployed person, as seen in Chart 3. If this isn’t saying something about supply, perhaps this is telling us something about demand. To illustrate my point, allow me to pose a question. Why do businesses hire? They hire when their current workforce either lacks a necessary skill set or when the workforce is insufficient in size to keep up with either current or expected demand. Without greater demand than the business can serve, now or in the future, there is no reason to hire. As such, I would argue that the strength in labor markets, via hiring markets, is reflective of exceptionally strong demand. How strong? Like I said previously, demand is currently strong enough that employers have two job openings per available job seeker.

Zeroing in on Inflation

There are many theories on the sources of inflation, ranging from the price and quantity of money via the Fed and its balance sheet, to fiscal impacts via tax-and-spend government policies, as well as inflation being derived from overly strong labor markets. In my opinion, each of these has at least some merit. That is, they all share some blame for inflation. While they all begin at different starting points, each ultimately arrives at the same destination, the intersection of supply and demand. That said, there is one variable that is particularly relevant at this juncture that I will take a moment to expand upon. That variable is wages.

The relationship between wages and inflation has basically two dynamics, the aggregate level and the bottoms-up individual worker level. First, the aggregate level of wages matters because it impacts the quantity of money available to be spent or saved. Aggregate wages can increase through wage growth, pay raises, or by the total number of employed individuals increasing. Now, aggregate employment gains are typically not inflationary, as more workers tend to contribute to greater supply along with the greater demand that is created by more money being available for purchases. The exception would be if the workforce grows while supply remains constant. In fact, growth of the labor force is one of two variables that explain virtually all real GDP growth, with the other being productivity.

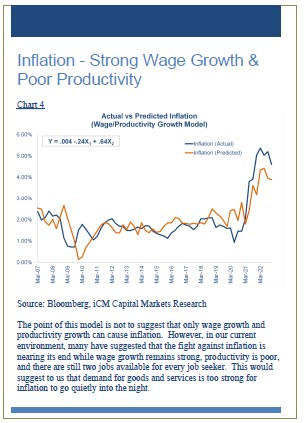

Wage growth, on the other hand, is a different matter. It is without a doubt correlated to inflation with the 1-year change in wages exhibiting a 0.65 correlation to 1 year inflation and the 3-year change in each variable demonstrating a correlation of over 0.80. Why? Well, in addition to the more dollars chasing around goods and services, wages are among the largest costs for most businesses. If wages increase, a business can either absorb those costs or pass them on to consumers, thus creating the linkage between wage growth and inflation, with one exception. If wage gains occur in the presence of productivity gains, that can blunt inflation. The reason…if a business can produce more with the same amount of labor they can afford to increase wages without increasing their prices. This can be seen in Chart 4. There are a few takeaways here. First, the equation shown in the chart represents the regression equation or the mathematical relationship between wages, productivity and inflation. In the equation, the second term(X1) is inflation’s sensitivity to productivity gains. The coefficient is negative, meaning as productivity increases, inflation, on the margin, is muted. The third term(X2) is inflation’s sensitivity to wage growth. The coefficient is positive, meaning when wages climb so does inflation. Notice the difference between the two. The wage coefficient is nearly three times the value of the productivity coefficient in absolute terms, indicating that productivity gains help, but have less of an effect on inflation than growing wages.

Wage growth, on the other hand, is a different matter. It is without a doubt correlated to inflation with the 1-year change in wages exhibiting a 0.65 correlation to 1 year inflation and the 3-year change in each variable demonstrating a correlation of over 0.80. Why? Well, in addition to the more dollars chasing around goods and services, wages are among the largest costs for most businesses. If wages increase, a business can either absorb those costs or pass them on to consumers, thus creating the linkage between wage growth and inflation, with one exception. If wage gains occur in the presence of productivity gains, that can blunt inflation. The reason…if a business can produce more with the same amount of labor they can afford to increase wages without increasing their prices. This can be seen in Chart 4. There are a few takeaways here. First, the equation shown in the chart represents the regression equation or the mathematical relationship between wages, productivity and inflation. In the equation, the second term(X1) is inflation’s sensitivity to productivity gains. The coefficient is negative, meaning as productivity increases, inflation, on the margin, is muted. The third term(X2) is inflation’s sensitivity to wage growth. The coefficient is positive, meaning when wages climb so does inflation. Notice the difference between the two. The wage coefficient is nearly three times the value of the productivity coefficient in absolute terms, indicating that productivity gains help, but have less of an effect on inflation than growing wages.

Now, like other post-financial crisis periods, productivity gains have been negative in 5 of the last 6 quarters on a year-over-year basis. Businesses are producing less but paying more. In this scenario, either profit margins suffer, or costs are passed on to consumers. Unless aggregate demand is highly elastic, price increases are the likely outcome.

Bank Issues and Inflation

The issues with the banking system are potentially serious, but there are many solutions. Since the topic of this letter relates primarily to inflation and the concept of a soft landing, I won’t get into that full explanation here. We have covered it in greater detail in our blog on our website if you are interested in reading further. That said, I would like to make a few key points to connect some dots.

The crossroads at which we find ourselves does not, at first glance, appear to be great place to be, as the solution to the banking crisis seemingly exacerbates issues with inflation. But does it really? To understand this better one must first understand the link between the Fed, interest rates, and Main Street. When the Fed hikes interest rates, there are many transmission mechanisms for that policy action to make its way onto Main Street. For example, as the cost to borrow becomes more expensive this has real world impacts on consumers of credit and is no more apparent than in mortgages and in car loans that used to be 2% and now may be 7%. Clearly, money spent on added interest payments is not available for other purchases. As we’ve covered in the preceding sections, less demand for other goods and services, as a result of spending those dollars on higher interest rate payments, will result in the intersection of supply and demand occurring at a lower price point (i.e., lower inflation). Or alternatively, as a result of the higher payment one may choose to eschew the purchase all together. Less demand for homes or for cars has the same effect.

In addition to impacting the consumer, higher rates in this case can impact a bank’s ability to lend. Banks are not typically risky investors. They make loans to consumers and invest in safe instruments like treasury bonds. However, when rates rise as they have, the value of those treasuries, if sold prior to maturity declines. This is normally not an issue except in extreme circumstances when depositors want their money back all at once. But, banks also compete for deposits with other non-bank entities. One can buy a money market mutual fund or invest directly in a short-term treasury. These competing products can draw loanable and investable capital away from banks, especially when they offer more attractive yields than bank deposits, just as they do currently. As depositors seek higher yields elsewhere this reduces banks’ capital available to loan, and a de facto tightening of financial conditions occurs. Perhaps these seemingly opposing issues, fighting inflation vs. helping the banks, are not as directly opposed as one would think? The de facto tightening that is occurring via less loanable assets, may actually be aligned with the fight against inflation, presuming it is sustained and not quickly reversed.

Summary

The title this quarter’s letter was The Soft Landing Façade. For a lot of reasons, winning this fight and engineering a “soft-landing” was probably more hope than reality. By definition, when supply is constrained demand is the only option. Throughout this quarter’s letter I’ve made the case that supply via the gains in the labor market and more directly as measured by total output do not appear to be the problem. We have more workers and a greater supply of goods available for sale than we did prior to COVID. However, with two jobs available for every job seeker, we believe that this is a sign of demand exceeding productive ability. In conjunction with this, wage gains have historically exhibited a high correlation to changes in inflation, unless offset by productivity gains. This allows businesses to reward workers without eroding profits or passing on higher costs. The effects of productivity gains are helpful, but only on the margin. Conversely, periods of high wage growth amidst declining productivity are typically highly inflationary, as businesses seek to pass costs onto consumers. Today, we have a combination of accelerating wages and low or negative productivity growth. A bad combination as it relates to inflation.

At the same time, higher interest rates have caused cracks to emerge in our banking system, leading some to wonder if the Fed will have to choose which battle to fight. While our initial reaction was to share this concern, we now have reason for optimism. As the ability and willingness of banks to make loans continues to feel pressure, this acts as a de facto tightening of financial conditions. Now, the intention is certainly not to create bank failures. That isn’t the goal nor can it be the side effect. But the two, inflation fighting and preserving the sanctity of our banks are likely more closely aligned than what it would first appear. Perhaps, while bumpy, this is all part of the landing process. Thank you as always for your continued trust and confidence.

1 William Edward Simon (November 27, 1927 – June 3, 2000) was an American businessman and philanthropist who served as the 63rd United States Secretary of the Treasury.

Market Insights is intended solely to report on various investment views held by Integrated Capital Management, an institutional research and asset management firm, is distributed for informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to constitute legal, tax, accounting orinvestment advice Opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. Integrated Capital Management does not have any obligation to provide revised opinions in the event of changed circumstances. We believe the information provided here is reliable but should not be assumed to be accurate or complete. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute a solicitation, offer or recommendation to purchase or sell a security. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investment strategies and investments involve risk of loss and nothing within this report should be construed as a guarantee of any specific outcome or profit. Investors should make their own investment decisions based on their specific investment objectives and financial circumstances and are encouraged to seek professional advice before making any decisions. Index performance does not reflect the deduction of any fees and expenses, and if deducted, performance would be reduced. Indexes are unmanaged and investors are not able to invest directly into any index. The S&P 500 Index is a market index generally considered representative of the stock market as a whole. The index focuses on the large-cap segment of the U.S. equities market.

For more news, information, and analysis, visit the ETF Strategist Channel.

Read more on ETFtrends.com.

The views and opinions expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Nasdaq, Inc.