The Economic Survey 2024-25 does a commendable job in highlighting the needs of the economy: deregulation, private participation, augmenting capabilities and energy transition as the four pillars of the growth edifice.

However, much as the strengthening of the pillars is required, the base of the “Stambh” requires equal attention: investment in human capital. Without investment in health and education increasing by a jump, the leap envisaged for the economy will not materialise.

First, the Economic Survey reports that 90.2 per cent of the workforce has equivalent to or less than a secondary level of education. This educational skill composition means most of the workforce (88.2 per cent) is involved in low-competency occupations, with elementary and semi-skilled occupational skills (Economic Survey, 24-25, p.398). The transition to higher incomes for the vast majority depends on upskilling.

Second, while the overall trend in earnings (across occupations and sectors) show a modest increase, there are signals of job loss and falling wages in the formal corporate sector. The profits of corporate India climbed 22.3 per cent in FY24, but employment grew by a measly 1.5 per cent, with employee expenses going down from 17 per cent in FY23 to 13 per cent in FY 24, indicating “cost-cutting over workforce expansion” (Economic Survey 2024-25, p.381).

This might be symptomatic of the low productivity of workers, which again highlight the need to upskill. While a host of government initiatives has been launched in recent years, majority of these are aimed to building vocational and entrepreneurial skills (Economic Survey 2024-25, p.374-75,401-407). There is simply much more to be done.

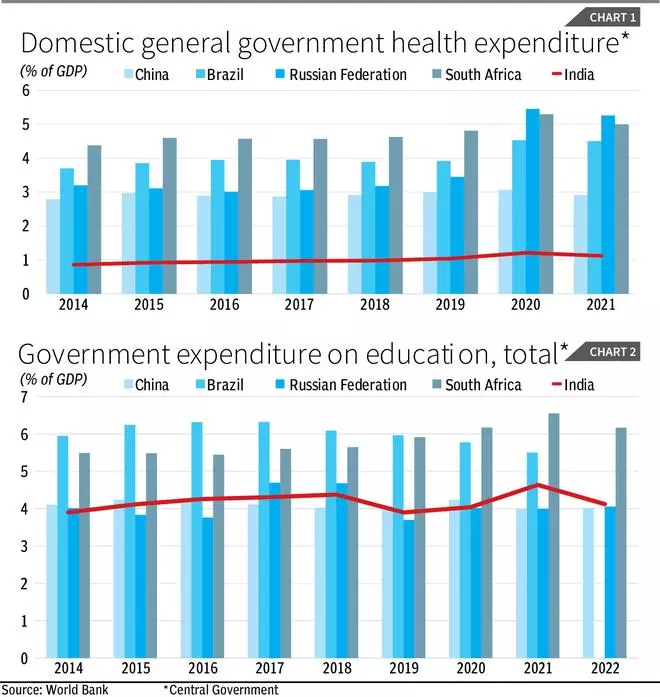

Compared to our BRICS peers, we have a distance to cover in terms of investment in education and health (as reported by World Bank). While comparison across nations, divergent in needs, is a simplistic tool, it gives a broad understanding of the importance accorded to the sectors. The cross-country comparison shows we spend less as proportion of GDP on education and health compared to most peers.

There has been some improvement in recent past: in FY25, our government expenditure on education and health is ₹9.2 lakh crore and ₹3.2 lakh crore (4.98 per cent and 3.33 per cent of GDP respectively). However, with a population base of 144 crore, the per capita expenditures are a drop in the ocean.

A structural problem

India’s spending on education and health has been historically low and it is stuck in a cycle due to structural problems. Roughly 35-40 per cent of the government revenue goes out for interest payments on outstanding borrowing, subsidies and defence spending. For example, these spendings, as reported in the 2025-26 Budget, have been 20 per cent, 6 per cent and 8 per cent, respectively (Key Features of Budget 2025-2026, Rupee Goes To, p.12).

Therefore, high fiscal deficit does not provide governments enough headroom for adjusting its revenues towards greater allocation to education and health. One primary way to address this concern would be to increase the tax revenue pie itself. The 2025-26 Budget announcement of no taxes up to income level of ₹12 lakh, however, does not look in sync with greater emphasis on human capital formation.

Why do we need more investment in health and education? First, skill development does not start at 18 years. India’s school education needs a complete overhaul to enable skill creation. Government schools serving more than 12 crore students with around 50 lakh teachers (Economic Survey 2024-25, p.308) lag the private school system in terms of infrastructure and quality. This is vouched by the fact that educating in a ‘private school’ remains an aspiration for parents who cannot afford it.

The faith on the public-school structure remains shaky and not without reasons. During Covid, educational attainment of millions of students in rural India came to a standstill due to lack of access to basic mobile technology: the unassertive action seen from Centre and State highlight the general lack of importance accorded to education.

For skilled employees to be created in the next 10 years with AI driven job roles across the value chain, an immediate focus on creating state-of-the-art IT infrastructure and training of teachers is required. The government schools are the primary channels for imparting education in rural India. Therefore, a roadmap to improve the government schools in terms of infrastructure and quality of education is the key to creating a skilled labour force.

Second, India’s higher education system, the largest in the world with 4.33 crore students, needs not just the creation of new IITs and IIMs every year, but also large-scale investment in research to step up to the changing skill requirement of industry. The difference in quality between top-rung and second order higher educational institutions is stark, creating a disparity in quality of educational attainment.

Health investment

Third, public health system needs sustained increase in investment: both to keep up to the effective provision of the many health care schemes announced and address challenges of the changing landscape of health emergencies. Equipping our hospitals, from smaller towns to the major cities, for public health emergencies needs to be a priority, undoubtedly requiring a steep scale up in investment.

Further the effective implementation of various schemes launched require Centre-State coordination, which is far from ideal in most cases.

While tax reliefs doled in the Budget are expected to give a boost to consumption expenditure, the loss in revenue should not impact spending on these crucial sectors.

Furthermore, to the extent education and health depend on State spending, it is important to incentivise States to spend in these sectors. Without augmenting capabilities in health and education, the upward momentum in growth envisaged from deregulation and private investment may not materialise.

Roy Trivedi is Associate Professor, National Institute of Bank Management; Das is ICICI Chair Professor, IIM, Ahmedabad. Views expressed are personal