March 22 is observed as World Water Day globally, emphasising the crucial role water plays in both economic and human development. In India too, the day is marked by raising awareness about the pressing issue of water scarcity. However, once the day passes, this critical concern often fades into the background. Meanwhile, news emerging from the water sector is frightening. On one hand, the availability of water resources for the future is steadily declining, on the other hand, water quality is deteriorating. Global groundwater extraction is increasing by 1-2 per cent annually and nearly one-fifth of the world’s aquifers are on the brink of depletion.

The low-cost traditional water bodies (tanks, ponds, etc) are disappearing at an alarming rate. With water scarcity escalating, some even predict that future wars could be centred around access to water. Why is this alarming prediction gaining momentum today? Do we have enough water to sustain future generations?

Reports published by well-known international organisations indicate that water scarcity is one of the most pressing global challenges today, affecting millions of people worldwide. As population growth and urbanisation expand, the demand for water continues to rise, placing immense pressure on already limited water resources. Over 2 billion people around the world reportedly lack access to safely managed drinking water and around 4 billion people experience severe water scarcity for at least one month each year. The frequency and intensity of water-related conflicts are also rising sharply.

India’s status

India’s condition is precarious. The NITI Aayog report on the Composite Water Management Index (2018) underlines that “India is undergoing the worst water crisis in its history”. It mentions that about 60 million people face high-to-extreme water stress in India; 40 per cent of people will have no access to drinking water by 2030; 75 per cent of people do not have drinking water on their premises; 70 per cent of water is contaminated and India is currently ranked 120 among 122 countries in the water quality index. Due to the consumption of contaminated water, nearly 2 lakh people reportedly die every year in India. Since water is essential for economic development, some projections indicate that 6 per cent of GDP will be lost by 2050 due to the water crisis.

Water riots are frequently reported in rural regions even during monsoon season due to poor arrangements for harvesting water. A study shockingly reveals that 150 million women labour days and ₹10 billion are lost annually just to fetch water. Large areas of crops are reportedly dying every year due to water shortages. The conflicts between head and tail-end farmers in the canal command areas in different regions in India are increasing due to water scarcity.

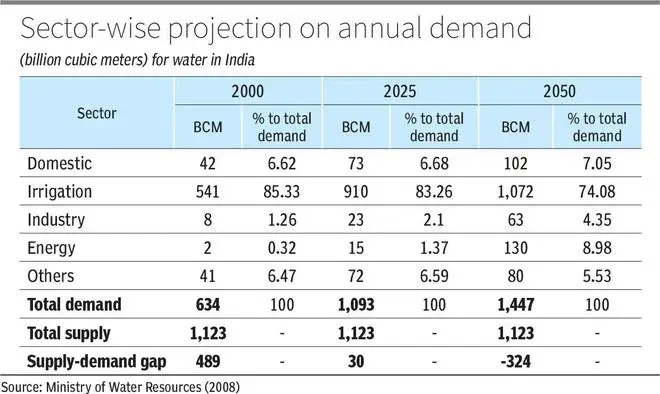

According to the Central Water Commission (CWC), India’s average annual utilizable water resource stands at about 1,123 billion cubic meters (bcm), but the demand for water is projected to increase at 1,447 bcm by 2050, leaving a huge supply-demand gap (see Table).

Continuous exploitation of water has caused a decline not only in total water resources but also in per capita water availability, which has fallen dramatically from 1,816 cubic meters (cum) in 2001 to 1,544 cum in 2011. This is expected to drop to 1,434 cum in 2025 (per capita water availability less than 1,700 cum is termed as water stressed condition).

A report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (2013) mentioned that water use has been growing at more than twice the rate of population increase in the last century, which is also expected to increase further due to various reasons. While the primary driver behind the decline of per capita water is population growth, the competing demand from various sectors is also putting more stress on water resources.

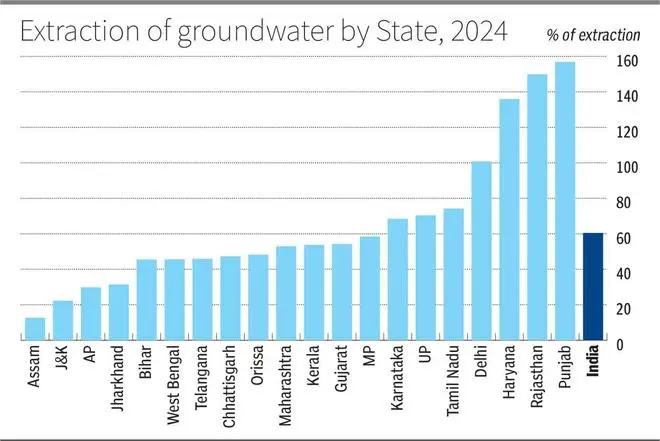

Groundwater, which contributes to 65 per cent of irrigation water, 85 per cent of rural water supply and 50 per cent of urban water supply, is also in stress today than ever before. From the annual extractable groundwater of 397.62 bcm, a total of 244.92 bcm is being withdrawn currently, reportedly the highest in the world. The exploitation of groundwater is very high in most agriculturally advanced States (see Chart).

The Central Groundwater Board (2024) reported that about 27 per cent of the 6,746 assessed blocks are either not safe or over-exploited, with the situation worsening rapidly.

The way out

To combat this alarming water crisis, reducing water consumption in agriculture could be the key as it currently consumes over 85 per cent of the water. Canal irrigation covers about 18 million hectares in India, but its water use efficiency is a mere 35-40 per cent because of the absence of a water accounting method. By introducing the water accounting method in early 2000, Maharashtra was able to increase the water use efficiency substantially. The inefficiency occurs largely due to the area-based pricing of canal irrigation water, instead of volumetric pricing. As recommended by the Vaidyanathan Committee (1992) on the pricing of irrigation water, volumetric pricing may help improve water efficiency in canal-irrigated area, reducing water scarcity within the canal-irrigated area.

One promising solution for increasing water use efficiency is micro-irrigation (drip and sprinkler irrigation). Field studies conducted across India have shown that these methods can save 50-70 per cent of water and electricity, while significantly increasing crop yields. While estimating India’s total potential area (about 70 million hectares) for micro-irrigation, the Task Force on Micro-Irrigation (2014) highlighted the huge water savings that can be achieved in different crops by adopting such technology. Maharashtra, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh have made rapid progress in the adoption of micro-irrigation. By expanding its adoption from the level of 16.74 million hectares in 2023-24, water use efficiency can be increased and groundwater exploitation can be curtailed.

India’s growing reliance on water-intensive crops such as paddy, wheat, sugarcane and banana, exacerbates the water scarcity issue. To address this, the government may announce increased procurement prices for less water-consuming crops with adequate procurement infrastructure. While addressing the demand-side issues, concerted efforts are needed to restore and renovate the low-cost source of small water bodies (tanks, lakes, etc) to augment the water supply.

A World Bank study cautions that the water scarcity exacerbated by climate change could cost up to 6 per cent of the GDP, spur migration and spark conflict. The increased water scarcity not only brings conflicts between the States and regions but also increases the cost of supplying water. Therefore, well-conceived supply augmentation and demand management strategies need to be introduced simultaneously to avoid looming water scarcity in future.

The writer is former full-time Member (Official), Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, New Delhi. The views are personal