A China-inspired growth strategy could help propel India to high-income status in next 25 years, says C Veeramani, Director, Centre for Development Studies (CDS), Thiruvananthapuram.

Key to this is accelerating labour productivity growth, he said while speaking at the CDS on ‘Industrial policy in the era of global value chains’ to commemorate First Development Researchers Day. China GDP per capital (2023) is $12,614 against a World Bank high-income threshold of $14,005 – which goes to mean China is on the verge of becoming a high-income country.

Global Value Chains

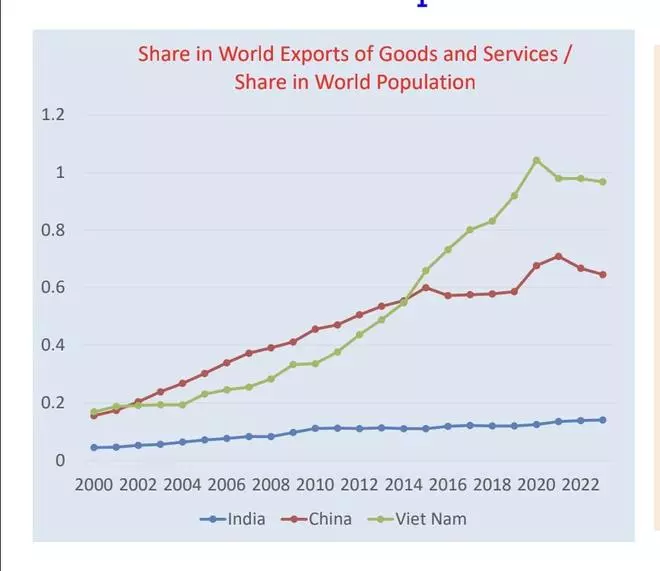

India in 2023 at best mirrors China in 2007 (per capita income) in growth sweepstakes. According to Veeramani, domestic market alone cannot drive medium-term growth, given the increasing debt burden for households, firms, and the government. The way forward is expanding outward orientation through global value chains (GVC), he explained.

The policy dilemma here is whether India should promote local linkages for domestic industries, or to participate in GVCs where in linkages are globally dispersed. The answer depends on the potential impact of these alternative strategies on domestic value added, productivity and employment, Veeramani pointed out.

Share in world exports of goods and services/share in world population

| Photo Credit: C Veeramani

GVC participation modes

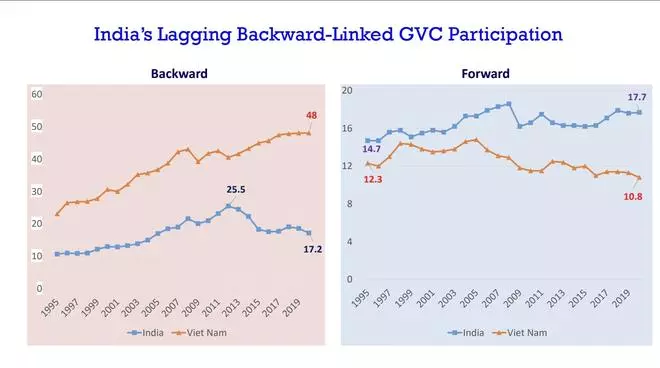

Referring to concepts of ‘backward’ and ‘forward’ GVC participation, he said in backward GVC participation, imported goods are used to produce for exports – as in exports of mobile phones or cars using imported parts. Forward GVC participation occurs when for example India exports iron ore to China where it is processed into steel, and then exported to other countries.

- Also read: FPI sell-off intensifies in February amid Trump trade effect

Veeramani said India has a comparative advantage due to its relative abundance of low-skilled labour. Assembly is labour-intensive, has potential to create millions for jobs for low-skilled labour. It also helps facilitate a Lewsian transformation, that refers to an economic model that describes process of moving surplus labor from agriculture to manufacturing.

Major growth driver

India’s lagging backward-linked GVC participation

| Photo Credit: C Veeramani

High backward participation (assembly) has been a major driver of China’s export growth, or that of Vietnam’s recent export growth; apparel exports from Bangladesh; and mobile phones from India. Although domestic value added per unit of export declines, gains arise because the absolute dollar value of domestic value addition and the number of jobs increase.

In the ‘wild geese flying’ pattern of GVC exports, Japan, the ‘lead goose,’ provided capital, technology, and managerial know-how to ‘follower geese’ nations in East and South-East Asia. Wild geese fly in orderly ranks forming an inverse V, just as airplanes do in formation. The GVC participation of several Asian countries depicts inverted V patterns, Veeramani said.

Targeted subsidies

Despite abundance of labour, effective cost of conducting assembly operations can remain high. This is due to rigidities in actor markets, institutional barriers, high input tariffs, high service link costs, and infrastructure bottlenecks. Reforms may be hindered by political economy dynamics. “Targeted subsidies can offset high effective costs and encourage GVC participation. For instance, PLI scheme for phone manufacturing,” Veeramani pointed out.

Hands-off approach

The best industrial policy may be none at all, Veeramani said using an aphorism that assumes government intervention in selecting specific industries to support through policy is generally ineffective and can lead to market distortions. A hands-off approach is preferable, letting the market decide without government interference.

The government must work to create a conducive environment – ensuring macroeconomic stability, improving infrastructure, enforcing fair competition – rather than directly intervening in market outcomes. Cost of a misplaced industrial policy is evidenced in resource misallocation and inefficiency, rent seeking, retaliatory dynamics or policy response, and trade tensions.

- Also read: Choosing the smart NPS exit option for a lucrative pension