Faced with Trump’s decision to withdraw from financing the defence needs of its alliance partners in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), and paranoid about Russian expansionism beyond Ukraine, Europe’s leaders have committed themselves to invest in their own ‘security’. That would require recruitment to enhance the size of its defence services, a substantial increase in defence procurement to build stocks of military equipment to catch up with potential enemies, and continuing expenditures to stay ahead.

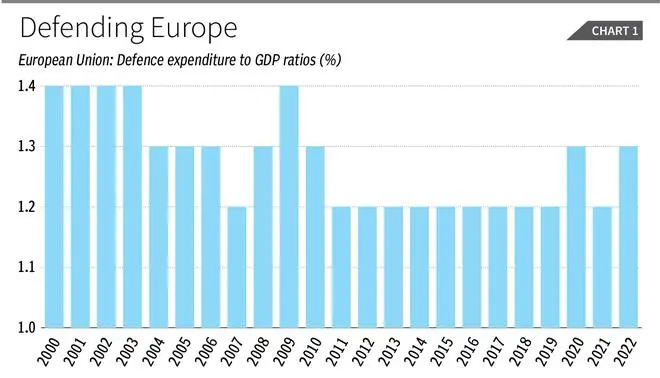

Defence expenditures in the European Union have hovered at around 1.3 per cent of GDP on average since the turn of the last century (Chart 1). Estimates of what it would take to make up for a US exit are in the range of 3-5 per cent of GDP, calling for a near- or actual tripling of spending.

That’s a tough call for a group of countries battling to meet the targets set by self-imposed austerity in the form of the convergence criteria specified as a part of the transition to a common currency and monetary union. The ‘fiscal rules’ adopted following the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 set a cap on the fiscal deficits of each member government at 3 per cent of GDP and a target of limiting public debt to 60 per cent of GDP. In the case of most countries in the grouping, that has proved difficult to realise or sustain.

Public debt path

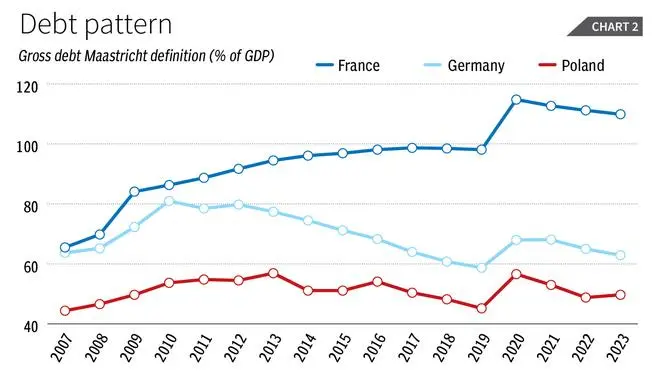

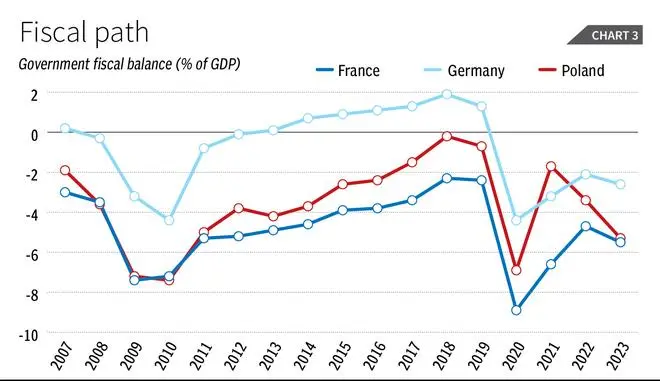

Charts 2 and 3 present figures on the levels of the fiscal deficit and public debt relative to GDP for three countries — France and Germany, the two largest, and Poland, which feels the heat from Russia the most.

Of these, Germany is the only one that has managed to keep within levels specified in the fiscal rules in all years since 2000, excepting for 2020 and 2021 when the Covid pandemic necessitated a spike in debt financed spending. Its fiscal deficit in 2023 stood at a comfortable 2.3 per cent of GDP.

In contrast, France has been able to ensure deficit figures at or below the Maastricht rule only in two years (2007 and 2018), with the deficit figure peaking at 8.9 per cent in Covid year 2020 and standing at a high 5.5 per cent in 2023.

Finally, Poland has been Maastricht compliant in terms of its fiscal deficit record in seven of the 24 years, and has recorded 5 per cent or more levels in 2011, 2020 and 2023. The high level in 2023 is because, fearful of Russia with which it shares a border, Poland, according to an estimate reported in the Financial Times, raised military expenditure from 1.98 per cent of GDP in 2019 to 2.23 per cent in 2022 and 3.83 per cent in 2023. That experience points to what financing defence with debt could do.

When it comes to debt-to-GDP levels, the record is slightly different. France has been way off target and Germany too has been delinquent in a number of years. The level of the deficit in these countries spiked in 2009 when the EU invoked an escape clause that permitted members to exceed the public debt target “to deal with a severe downturn” when faced with “major shocks to the euro area or the EU as a whole”.

Debt brake

The public debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 81 per cent in Germany in 2010, and to 86.3 per cent in France. Germany decided to pull back and instituted a “debt brake” that limited new public borrowing to 0.35 per cent of GDP a year. But France chose to stay with the violation, resulting in an increase in the figure to 98.7 in 2017.

The next spike occurred when the pandemic led to increased debt financed spending, raising the public debt to GDP ratio to 114.8 per cent in France and 68 per cent in Germany in 2020. Germany has since pulled back, but France is still overextended by Maastricht standards. Compared to these countries, Poland has been more conservative, well within the EU target for borrowing, but as suggested by its fiscal balance figures, a recent hike in defence spending may change that picture.

Return to Keynesianism?

This has led to animated discussion across Europe on whether the decades-old adherence to fiscal conservatism should be given up, and debt should be relied on as a means to beefing up defence in the new era. Some have suggested that this presages a return to Keynesian-style fiscal policy. There does appear to be a consensus that this is the way to go.

But the long-term advocacy of neo-liberal and conservative fiscal principles, and the strong backing this ideology receives from the dominant epistemic community of finance, militates against the transition.

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte’s plea for a diversion of just “a small fraction” of national spend on pensions and health to defence found few takers. Germany’s Finance Minister Christian Lindner faced opposition when he advocated freezing social spending for three years to extract finance for defence. And European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s decision to invoke the “escape clause” that permits enhanced borrowing has yielded relatively small sums thus far.

This persisting fiscal conservatism can inflict collateral damage. The problem Europe faces is that the pressure to raise defence spending is too strong to ignore. But proposals to mobilise resources by imposing taxes on the very rich face strong opposition from a powerful elite represented by rising conservative forces.

Given that, the only alternative to deficit spending as means of raising the relevant expenditures, is a restructuring of the spending budget, that takes away resources from some other sectors to enhance defence expenditure.

In Europe, health (7.6 per cent of GDP in 2022), education (4.6 per cent), and social protection (19.2 per cent) do receive higher proportions of expenditure relative to GDP when compared with many other countries.

So, a lazy way of boosting defence would be through a reduction and diversion of welfare spending. There are several conservative voices making that case. But having been accustomed over many years of state support for health, education and social protection, the working and middle classes are bound to protest. Europe’s need to rearm to face threats from abroad may well set off wars at home.